Ocean Shore Railroad

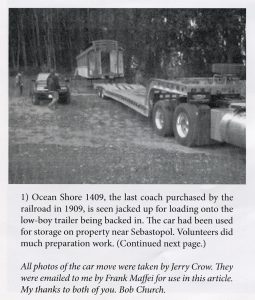

Much of Pacifica’s layout owes its beginnings to a small, little-known railroad company. Incorporated in 1906, the Ocean Shore Railway Company planned to run a high-speed electric railway between San Francisco and Santa Cruz. To attract weekend excursions and tourists, the route would hug the shoreline as closely as possible. That decision was probably its undoing.As part of California’s coastal history, this rail car brings the City of Pacifica a tangible link to its history. Car #1409 was the last purchased by the Ocean Shore Railroad, and ran on rails from San Francisco through Daly City to the coastal towns of Pacifica, Montara, Moss Beach, Princeton, Granada, Half Moon Bay and beyond with connections to Santa Cruz.

Disaster Strikes

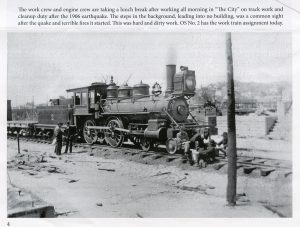

Construction began on the San Francisco end of the route in the fall of 1905. Railroad building had just reached Mussell Rock, where the San Andreas fault dives into the Pacific Ocean, when disaster struck. Early in the morning of April 17, 1906, an 8.1 earthquake started a rockslide above the new rail line. Ocean cliffs collapsed, dumping over 4,000 feet of railroad track, along with rolling stock and construction equipment, into the sea. Huge cracks opened up along the roadbed. Of the track that remained, much was twisted and contorted to such a degree that it resembled a roller-coaster. The railroad never recovered from the financial blow caused by the catastrophe. Investors dropped out, and, with less money, the directors decided to substitute a single-track steam line for the planned two-track electric railway.One hundred years ago, the Ocean Shore Railroad ran through our scenic coastal community, meandering along cliff sides and past lush farm fields, carrying city dwellers, who for the first time were able to visit our beautiful coastal area. Many of these visitors liked the area so well that they became the first settlers, buying land offered by the Ocean Shore Railroad realtors.

Construction Resumes

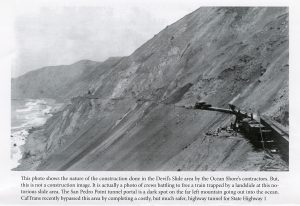

Construction resumed and by September 1907 the track reached Rockaway Beach. There, they laid track on a ledge cut above the ocean that rounded Rockaway Point, headed uphill to Tobin station (San Pedro Point) and met one of the most difficult engineering obstacles on the entire line-the solid rock of Point San Pedro. First a ledge was cut into the cliff face from Tobin station to Shelter Cove. Then they bored a tunnel through the point itself. To get supplies and materials to the site, they anchored a ship offshore and transported materials along an aerial tramway. The railroad was rapidly running out of time, money and patience. To create a level bed for tracks on Devil’s Slide, they stuffed nine tons of black powder into a specially constructed tunnel and literally blew the top off the mountain. Instant roadbed.

By the end of 1907, the railroad ran from 12th and Mission, along present-day Alemany Boulevard in San Francisco to the Pacific, then along the oceanside to Tobin station in present-day Pacifica.

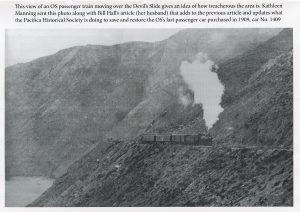

The Route Through Pacifica

The railroad line had several stops in Pacifica-Edgemar, Salada, Brighton, Vallemar, Rockaway, Tobin-before plunging into a 354-foot tunnel through San Pedro Mountain. It resurfaced at the edge of the high cliffs, 700 feet above the crashing surf. This dramatic ride caused a great deal of trouble for the rail line, because the roadbed was built on an unstable piece of shifting mountainside known, appropriately, as Devil’s Slide. Numerous slides damaged the roadway. One landslide, on January 15, 1916 closed the line for more than two months and required over $300,000 in repairs.

The round-trip fare averaged about 20¢ (based on the purchase of a $5 monthly ticket). Excursion trips were popular. On Sundays, the railroad supplemented the traditional cars with open flat cars topped with picnic benches.

The trip from San Francisco to Salada Beach took 57 minutes, though it was advertised as taking 25 minutes. Unfortunately, the trains were often delayed. Travel was often interrupted by the results of a heavy rain that caused culverts under the tracks to jam with debris, washing away the roadbed. Local wits maintained that all it took to cause a washout on the Ocean Shore was a good heavy fog, and there was always plenty of that.

Never Completed

Rail lines ran from San Francisco south to Tunitas Glen and from Santa Cruz north to Swanton. The middle leg of the line, 26 miles between Tunitas Glen and Swanton was never completed. Passengers wishing to continue disembarked from the train and boarded a special Stanley Steamer to reach the railhead at the other end. Four trains (two round-trips) ran daily and six on Sundays and holidays.

The Real Estate Game

The Real Estate Game

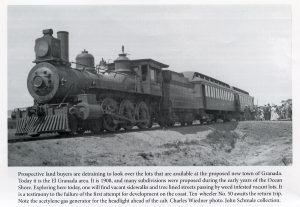

A major impetus for the railroad was the real estate game. Fast-talking promoters lured city-weary prospects to the coastside by offering free trips on the railway, open air concerts and free lunches. The ads claimed that the towns had “no taxes and no saloons.” Salada Beach, near the natural lagoon known as Laguna Salada (in the Sharp Park golf course), was designed to be a major watering hole. Ads extolled its allure and the “beautiful, balmy climate.” A promenade, bandstand, casinos, cafes and several large hillside hotels were envisioned surrounding the lake, which was much larger than the present size. Of those grandiose plans, only the bath houses on Clarendon Avenue and the concrete pillars for a dance pavilion in the center of the lagoon were built. Lots sold at Salada Beach started at $250 for a 25 x 50 foot parcel. You could get one for $10 down, $3 a month. Nearby Vallemar was a bit pricier. There, you needed a $5 down payment.

Vegetables Galore

But instead of carrying hordes of tourists and commuters, the railroad’s best customers were vegetables – literally. Artichokes, beans, Brussels sprouts, peas, potatoes and other coastside produce were in high demand. Most ended up in East Coast homes and restaurants. Coastside farmers were paid 5 1/2 ¢ a choke. Artichokes went for 75¢ each in New York.

The End of an Era

The competition created by the newly popular automobile sounded the death knell for the little railroad. It had rarely made a profit and, in 1920, was forced to stop operations. Most of the Ocean Shore right of way was paved over and turned into Highway 1, reputed to be the most spectacular road on the West Coast.

Railroad Sights in Pacifica Today

Railroad Sights in Pacifica Today

Rail buffs can still see signs of Pacifica’s early railroad days. Portions of the right of way can be seen along the Rockaway headlands and along the railway berm in Pedro Point. The huge cut between Fairway Park and Vallemar was blasted out by railroad engineers. Three railroad stations still stand. One is camouflaged as the ERA Dolphin Real Estate office at the corner of Manor Drive and Oceana Blvd. One is now the Vallemar Station Grill, located at 2125 Coast Highway. The third is Tobin Station on San Pedro Point (corner of Danman Avenue and Shelter Cove Road). The former outdoor shelter was enclosed many years ago and is now a private residence.

The Legacy of The Ocean Shore Railroad by Bill Hall

Article featured in the Western Railroader #713

While the Ocean Shore Railroad was being built, local papers of course, carried accounts of the construction progress. After the 1906 earthquake, the progress of the little railroad had come to the attention of the nation. The publicity department produced large colorful broadsides and posters ex-tolling the beautiful beaches and other attractions.

Planned resorts were pictured on post cards, posters and brochures showing an entertainment complex to rival New York’s famous Coney Island and a huge casino to be built at Salada Beach. But, as with most of the other fantastic beach developments, they failed to materialize beyond the artists conceptions.

The railroad actually constructed model homes south of Pacifica and laid out an especially elegant town plan with wide streets. Lots were at first generally sold closest to the depots. Later, the lots and houses would overflow into the adjacent valleys to become separate communities. In 1957 they all became Pacifica.

Weekend passengers had flocked to the beaches on good days, but at other times the trains were virtually empty. The end of the Ocean Shore Railroad started with the arrival of the automobile, at the very time the railroad was financially being forced to cease operations.

Weekend passengers had flocked to the beaches on good days, but at other times the trains were virtually empty. The end of the Ocean Shore Railroad started with the arrival of the automobile, at the very time the railroad was financially being forced to cease operations.

The publicity of the beautiful coast side and the public who just visited and later settled changed our area forever, even the roads we drive on are often built upon the old railroad tracks. There are two stations still existing and a levee.

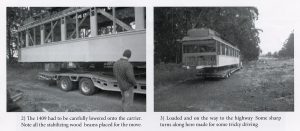

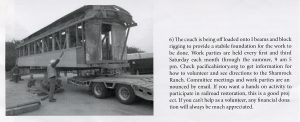

Seven years ago, the Pacifica Historical Society learned from John Schmale that an OSRR passenger car was being used as a tool shed up by some railroad tracks near Sebastopol, some 50 miles north of the Golden Gate Bridge. Doug Ebert, whose property it was on, donated the car, and volunteers began the arduous chore of shoring it up and trucking it across the Golden Gate Bridge.

Restoration work by historical society volunteers, supported by our fund raisers, has continued for seven years. The work has been slow, because they are also restoring another original, the Little Brown Church in Pacifica, as a history museum and event center. Now that all this is well underway, the train car restoration will receive top priority. More volunteers and more donations, will of course, speed things up.

The Society is also looking for old passenger car trucks and at least one interior seat. When completed, the car will hold the Society’s working model of the Ocean Shore RR in Pacifica – a spectacular HO scale display built by the Vargas Brothers.

The Society hopes that the train car will finally rest next to the Little Brown Church just as it did 100 years ago, a wonderful tourist attraction in our little picturesque town where the mountains reaches the beaches.

If you want to learn about Pacifica, about the Pacifica Historical Society and see who we are and what we are restoring; go to our website at: pacificahistory.org. All work can use financial support too!

Ocean Shore Railroad by John Schmale

Article featured in the Western Railroader #713

The Ocean Shore Railway started construction on May 18th, 1905 on what was to be a double track electric line to run about 83 miles from 12th & Mission Street in San Francisco to Santa Cruz. The San Francisco charter allowed for electric-only operation, so the Ocean Shore was forced by circumstance to use electric power in the City of San Francisco until the end in 1920.

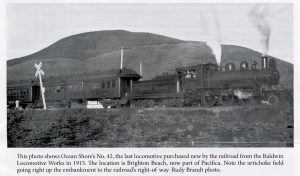

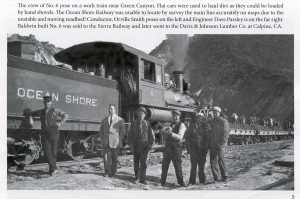

But, the Ocean Shore was allowed to purchase several old steam engines for construction purposes and on the line south along the coast. If the railroad eventually had three electric freight motors for operation in San Francisco proper, and they did have as many as ten steam locomotives at one time. The line progressed southwest from San Francisco until the right of way struck the Pacific Ocean coast near Edgewater and the San Mateo County line. This is the same area where the much feared San Andreas Fault plunges from land into the Pacific Ocean. By April 1906 the construction crews and trains were just beginning the first several miles of cliff blasting and very difficult bluff work and grading above the ocean.

Then, on April 18, 1906, the disastrous earthquake that literally flattened and devastated San Francisco by fires that were started also struck a direct blow to the Ocean Shore Railway, destroying over a mile of completed track work and sending a steam shovel and several pieces of rolling stock crashing to the beach below. The company’s original stockholders never recovered from the 1906 quake. The company was forced into receivership during 1911. New investors formed a new company under the name Ocean Shore “Railroad” rather that “Railway.” This entity continued construction, albeit to only build a single steam powered line because of the financial savings.

Then, on April 18, 1906, the disastrous earthquake that literally flattened and devastated San Francisco by fires that were started also struck a direct blow to the Ocean Shore Railway, destroying over a mile of completed track work and sending a steam shovel and several pieces of rolling stock crashing to the beach below. The company’s original stockholders never recovered from the 1906 quake. The company was forced into receivership during 1911. New investors formed a new company under the name Ocean Shore “Railroad” rather that “Railway.” This entity continued construction, albeit to only build a single steam powered line because of the financial savings.

Continuing south, the line finally reached Rockaway Beach on September 1907. Beyond there the line headed uphill to where the construction crews encountered one of the most difficult engineering obstacles on the entire line, the solid rock of Point San Pedro. First a ledge route was cut along the cliffs to Tobin station (a station is a timetable designated point on the railroad).

Beyond Tobin a tunnel had to be bored through the point itself and beyond the tunnel, the rails had to traverse the face of Devil’s Slide. To this day, the Devil’s Slide area has been a source of very costly maintenance, then for the rail line, and now for Hwy 1. Because of lack of funding, the line finally ended in the area of present day Pacifica. At the time, the planned line continuation to, several small hamlets along the line north of the tunnel included Salada Beach, Brighton, and Vallemar. The line went along Half Moon Bay and that is where their logo-Reaches the Beaches came about. Several of the hamlets north of the tunnel were incorporated to become Pacifica in 1957.

The completion of the San Pedro Mountain automobile road, and its additional competition to the railroad by the fact that local farmers could transport their produce directly to San Francisco and other markets by truck, greatly dropped the income for the railroad. The line finally ceased operating scheduled trains after August 27, 1920 and was abandoned on October 20, 1920.

At the same time the company investors were building the line south from San Francisco, they were also building their line north from Santa Cruz to connect with the San Francisco extension. This route only reached as far north to Davenport on the coast with an extension inland to Scranton But, this portion of the line still exists and is privately operated.

Sources

- “Salada Beach”, Western Realty Company, date unknown (probably 1907 or 1908)

- “Salada: The Beach in Reach”, Ocean Shore Land Company, 1908.

- “Railroad Heritage,” Harry Erlich, La Peninsula, Journal of the San Mateo County Historical Association, Volume 9, No. 1, February 1961.

- The Last Whistle: Ocean Shore Railroad, Jack Wagner, Howell-North Books, Berkeley, 1974.

- Barbara VanderWerf, Granada: A Synonym for Paradise – The Ocean Shore Railroad Years, Gum Tree Lanes Books, El Granda, 1992.

- “Rum and a Railroad-How Salada Beach Grew”, Tom Johnston, Pacifica Tribune, November 9, 1977.

- The California Highway One Book, Rick Adams and Louise McCorkle, New York: Ballantine Books, 1985.

- Half Moon Bay Memories, June Morrall, Moonbeam Press, El Granada, 1978

- Western Railroader – May/June 2013 – WRR #713

- CityofPacifica.org – 1996, June Langhof